Kids Born Out of Fire: On Ari Marcopoulos’ Polaroids (92-95)

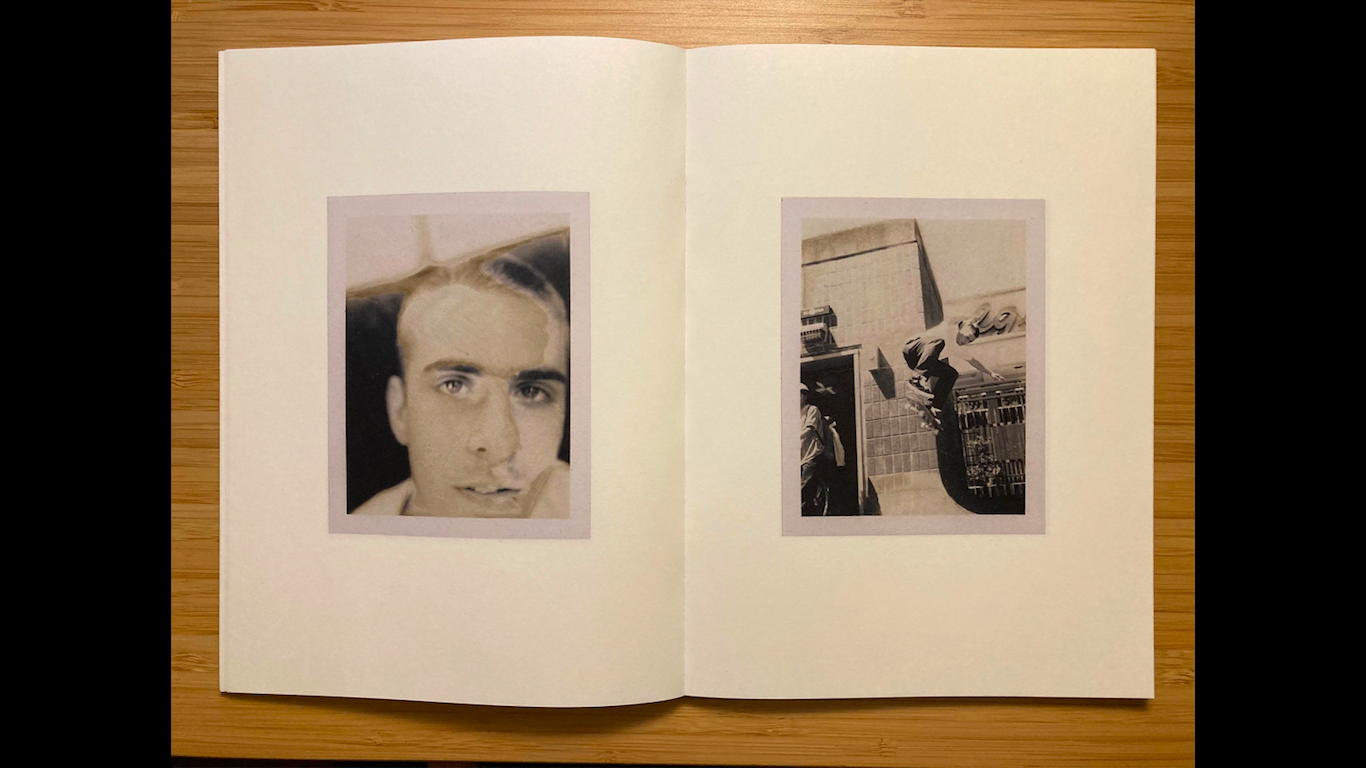

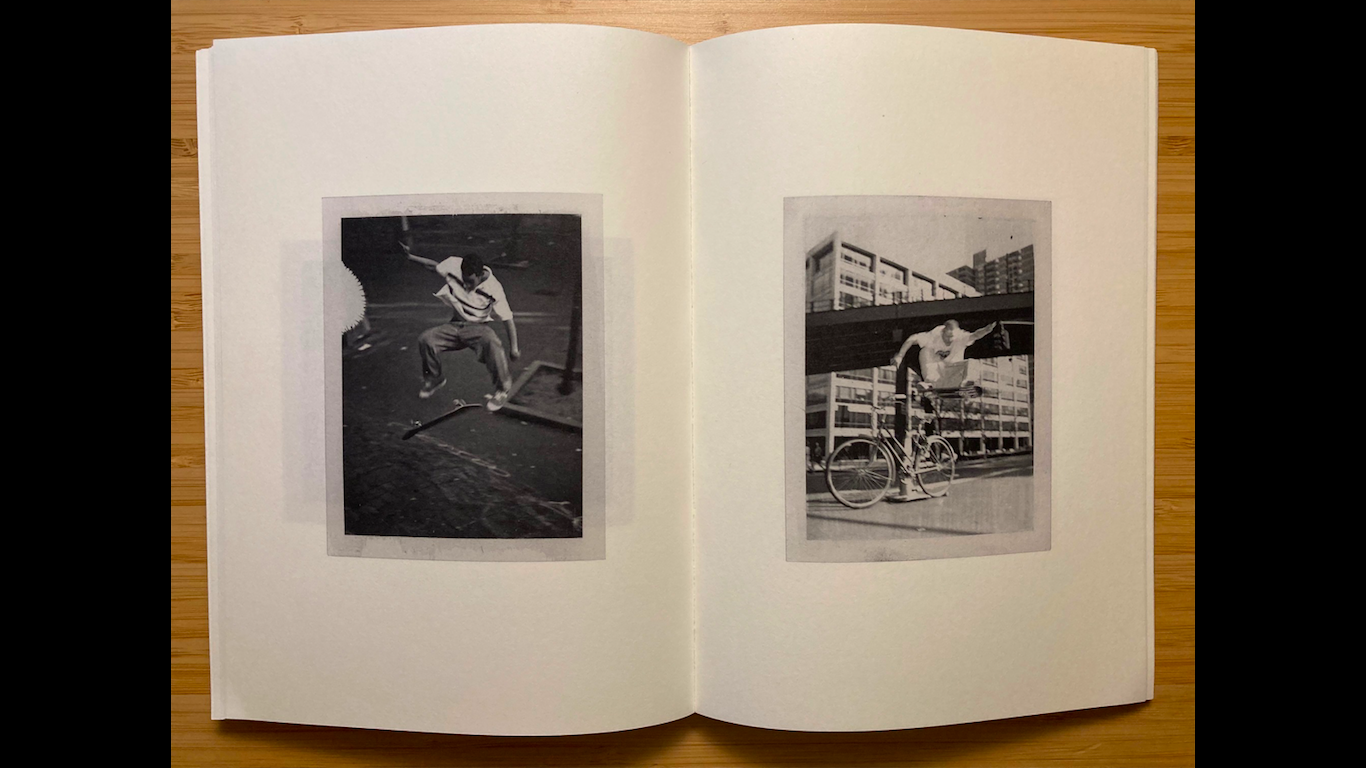

Skate photos take on an unusual mystique in Ari Marcopoulos’ latest books, Polaroids 92-95 (NY) and it’s companion volume, Polaroids 92-95 (CA), both out from Dashwood Books. In these publications, we find a tender, if disjointed montage of images: the past, but more ambient, interstitial, and awkward than anyone remembers it. Your favorite pros, but greener, skinnier, and more self-conscious. A primary document, but made up of curious outtakes. A handful of skate photos, but nothing was landed (except, maybe, an ollie over a bike by Julien Stranger, and a Japan air by Max Schaaf). It’s skateboarding’s golden era, but as three years worth of empty afternoons, and a guy with a new Polaroid camera—part of the fascination arising from the irony that it took 25 years for these images to come to light, when Polaroids develop instantly.

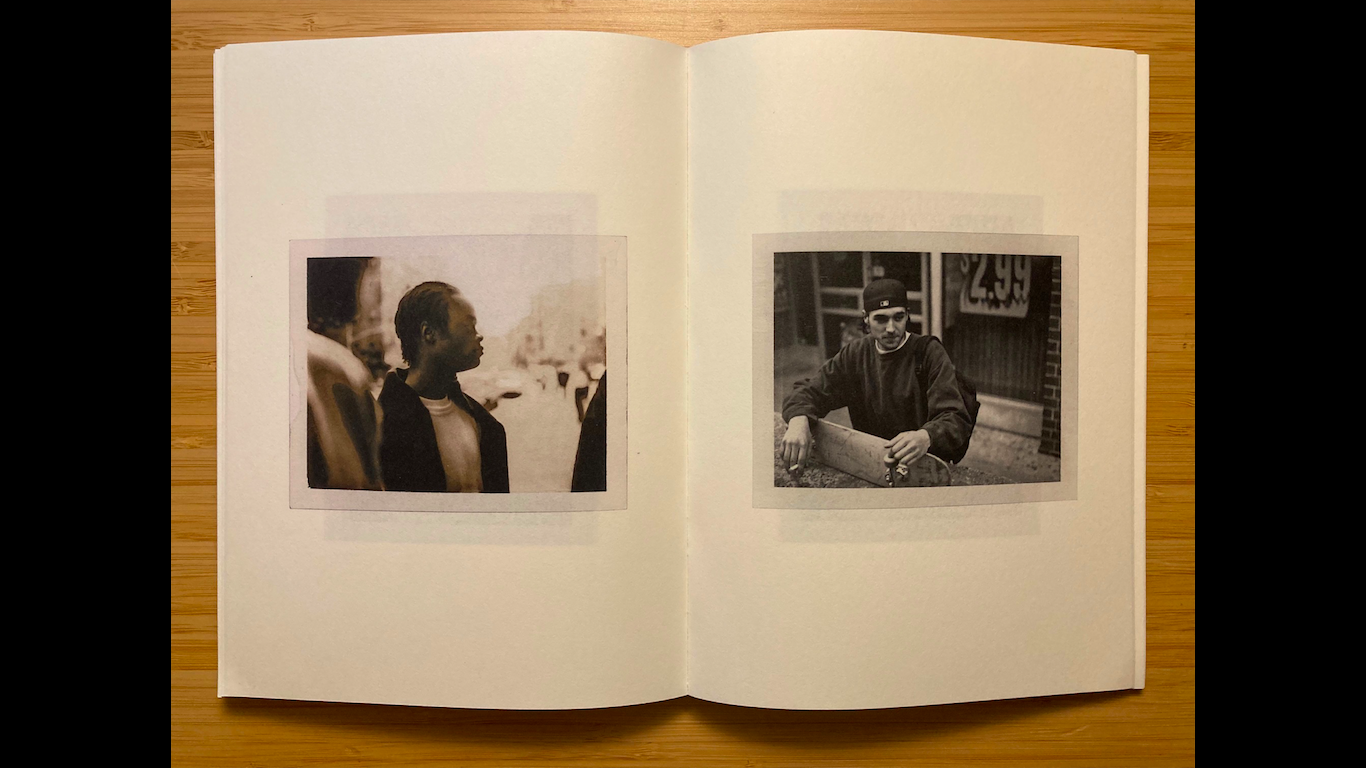

Marcopoulos has been shooting skate photos for decades, and his idiosyncratic style of image making clearly borrows from the mythologizing eye skaters turn to spots: granular, obsessed with inscrutable details, highly attuned to place, attracted to the fringes and other peripheral places—materialist, but still chasing a spectacle. In other words, Marcopoulos will hone in on the most mundane, obscure, in-between places—airports, the underside of bridges, stairwells, gutters, litter, youth—dipping in and out of the all-consuming flood of images that already populate our world.

Marcopoulos has been shooting skate photos for decades, and his idiosyncratic style of image making clearly borrows from the mythologizing eye skaters turn to spots: granular, obsessed with inscrutable details, highly attuned to place, attracted to the fringes and other peripheral places—materialist, but still chasing a spectacle. In other words, Marcopoulos will hone in on the most mundane, obscure, in-between places—airports, the underside of bridges, stairwells, gutters, litter, youth—dipping in and out of the all-consuming flood of images that already populate our world.

The same maleability plays into his publications, as well, perhaps best represented by Anyway (Dashwood Books, 2012): no stranger to the expediency of self-publishing and zines, the unorthodox tome collects a few dozen of these saddle-stitched booklets, and presents them in a beige archival box, mounting a de facto catalog raisonée as a figment of coherence, a monument to the gloriously incidental; easy to store, impossible to archive.

How that slipperiness fits into these books is quite interesting. The Polaroids were taken between 1992-95 in New York and San Francisco, respectively, but were subsequently lost for the last 25 years, only to be rediscovered in 2020. Yet, despite what we might hope for such a momentous rediscovery, as Marcopoulos explains in his dedication, much information remains forgotten. This detail is important, because it’s what I imagine aligns these books with skateboarding’s fundamental antipathy toward officialdom, and its predisposition to such lost tales and minor histories as ABDs, NBDs, BGPs, sticker-based memorabilia, the Slap Message Board, and a world of conflicting opinions about who did what when, and why Ricky Oyola claims that Vinnie Ponte was not the first person to ollie down Love—basically, all the bullshit that marks skateboarding as an oral tradition.

How that slipperiness fits into these books is quite interesting. The Polaroids were taken between 1992-95 in New York and San Francisco, respectively, but were subsequently lost for the last 25 years, only to be rediscovered in 2020. Yet, despite what we might hope for such a momentous rediscovery, as Marcopoulos explains in his dedication, much information remains forgotten. This detail is important, because it’s what I imagine aligns these books with skateboarding’s fundamental antipathy toward officialdom, and its predisposition to such lost tales and minor histories as ABDs, NBDs, BGPs, sticker-based memorabilia, the Slap Message Board, and a world of conflicting opinions about who did what when, and why Ricky Oyola claims that Vinnie Ponte was not the first person to ollie down Love—basically, all the bullshit that marks skateboarding as an oral tradition.

The result, however, is that fact and fiction narrow significantly when we look at these images. On the one hand, we get a semi-factual account of street skating’s prelapsarian period, prior to its eventual corporatization—a real time, and a real place. But on the other, the kids in baggy pants and skate companies ripping their logos from athleticwear; hats worn exclusively backwards with offensive t-shirts; the mishmash of street and vert, East coast and West; and the gawky body language of adolescence, together frame out a version of Neverland, wherein all the details of this world are stand-ins for desire and yearning—a world of profound moodiness and affect.

It’s this elusiveness that makes me think of Hollis Frampton’s 1971 film, Nostalgia. For one, like Marcopoulous, Frampton starts with the discard pile, focusing on 13 images from the filmmaker’s early days as a budding artist/photographer. And two, the film brings memory into question, pairing each image with a voiceover in which Frampton remembers the photograph’s various failures to launch as art, editorials, portraits, evidentiary documents, posters, and even objects. The trick, however, is that the subsequent montage is totally out of synch: the voiceover never corresponds to the image on screen, though it doesn’t prevent a certain sentimentality from blossoming as we watch the photographs slowly burn up on the coils of an electric hotplate. Nostalgia, it reveals, works on everyone.

It’s this elusiveness that makes me think of Hollis Frampton’s 1971 film, Nostalgia. For one, like Marcopoulous, Frampton starts with the discard pile, focusing on 13 images from the filmmaker’s early days as a budding artist/photographer. And two, the film brings memory into question, pairing each image with a voiceover in which Frampton remembers the photograph’s various failures to launch as art, editorials, portraits, evidentiary documents, posters, and even objects. The trick, however, is that the subsequent montage is totally out of synch: the voiceover never corresponds to the image on screen, though it doesn’t prevent a certain sentimentality from blossoming as we watch the photographs slowly burn up on the coils of an electric hotplate. Nostalgia, it reveals, works on everyone.

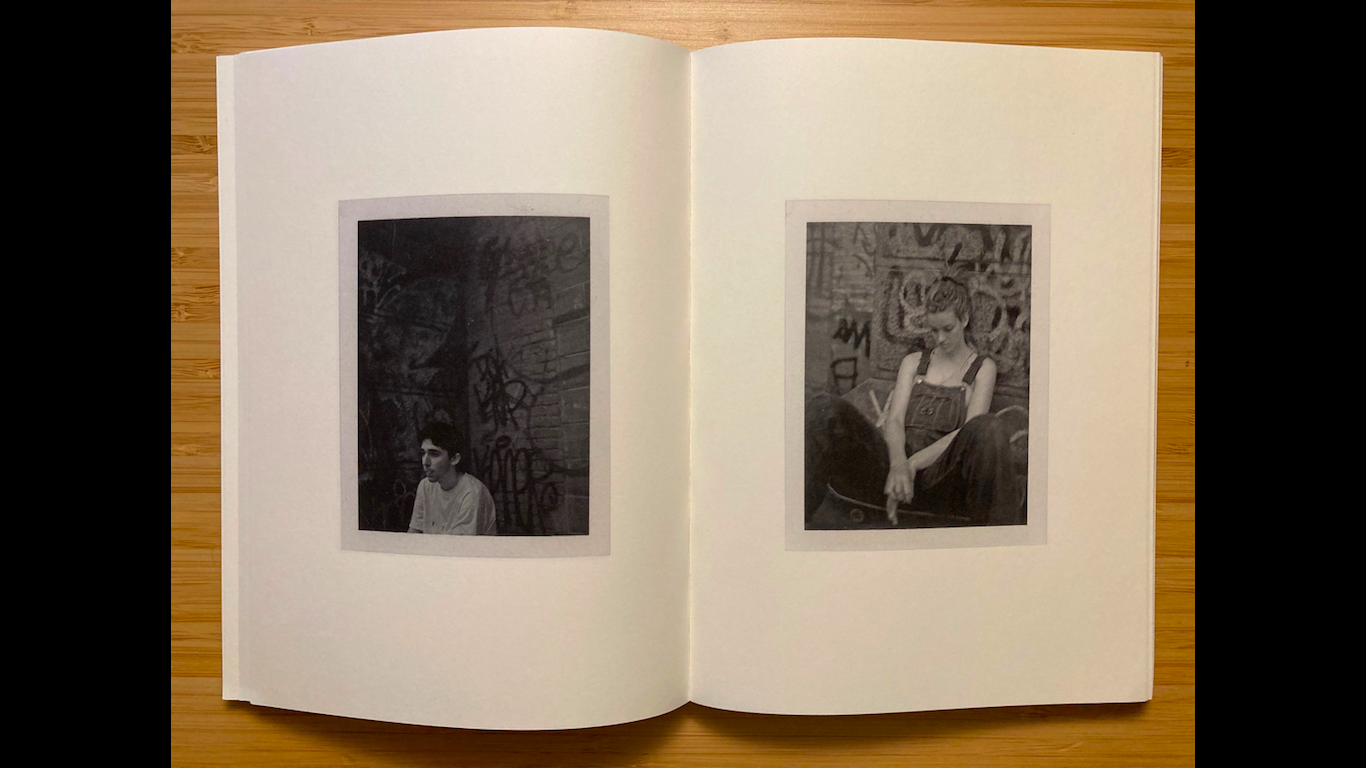

In the end, as much as I still have questions—where is Ethan Fowler these days? And who are the 2 or 3 women that occasionally populate these images? Dirty overalls, bushy ponytail, impassive expression, as angst-ridden and adventurous as any of the boys—their presence is so powerful, that all the other images seem to pile at the womens’ sneaker-clad feet—I bring up Nostalgia in relation to Marcopoulos’ Polaroids not to suggest that we will find answers, but rather, to describe how, everytime we look at them, our gaze seems to be drawn elsewhere—to the fringes of an image, the edges of an era, the heart of myth, or simply into a fairly normal past. In other words, in skateboarding, there’s often no difference between myth and fact. And that’s the fun of it. •••